“Our principle is… to seek peace.”

George Fox, Founder of the Quakers, 1661

Born from a country ravaged by civil war and religious combat, the Quaker movement dedicated their time and resources to advocating a message of peace and acceptance. One of their most articulate and effective members was actually a former soldier. William Penn, after being sucked into war in Ireland, found the Quaker movement and determined that his life’s work should be the establishment of peace. This evolved into his dream of a new colony, founded on Quaker principles of tolerance, religious freedom, and diversity. This involved populating his land with people who held the same principles and creating a government to protect them. Pennsylvania was the only colony who did not maintain a militia, who tried for years to refuse sending soldiers to fight in England’s wars, and established friendships with the native inhabitants of the land.

In this, Penn was extremely lucky. The Lenape Indians who resided here were known in the native communities as peacemakers. In wars between tribes, it was the Lenape who would often step up and broker a peace agreement. So when Penn arrived to make friends and trade fairly for the land, the Lenape were willing to become friends. The land westward, previously occupied by the Susquahannocks, had been vacated, so the Delaware Valley Indians were willing to relocate.

Even though his passion was Pennsylvania, Penn never stopped believing in the possibility of peace throughout the Old World. In 1693, he wrote “An essay towards the present and future peace of Europe” advocated for an end to the political violence. Penn was not always successful in what he advocated, but peace and tolerance continued to be a dominant trait in his government and in the Quaker people’s beliefs.

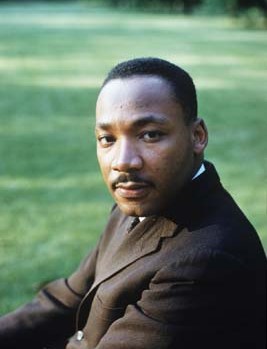

We honor the countless individuals, known and unknown, who struggled and sacrificed alongside William Penn and Martin Luther King Jr. to create a better world for the generations to come!

Hannah Howard, Volunteer & Special Project Coordinator