Last week, we shared the story of the Mattson Witch Trial, the only known witch trial William Penn presided over. Pennsylvania never reached anywhere near the heights of Salem’s infamous witch hunts. So just how much did Penn’s ideals make a difference in the witch hysteria?

The answer lies not within one difference, but many differences. Penn and his Quaker colony had a very different social environment influenced by religion, politics, and education. Penn founded his colony as a “holy experiment” grounded in his plans for religious tolerance, laws created and governed by the people, and a fair justice system. These values changed how witch hysteria affected the communities in Pennsylvania.

Much like the Quakers, Salem’s Puritan founders created their community out of a desire to escape religious persecution in Europe. However, contrary to Penn’s policy of inclusion and tolerance, Salem prohibited any non-Puritans from living in Salem.

Salem also had a history of persecution for witchcraft. The religious leaders regularly gave sermons warning of the danger of witches and openly advertised the witch hunts that happened throughout Europe. In addition, the court system did not really function and failed to regulate or protect those accused of witchcraft. So in 1692, when the accusations and trials really began to engulf the community, the colony’s government failed to maintain order and sanity.

- Anonymous drawing of witches at work from Johann Geiler von Kayersberg, 1517. Cornell University Library.

All of these factors play into the horrible persecution of the 59 people tried in Salem, of which 20 were put to death before anyone could stop the hysteria. By the end of the summer in 1692, 13 women and 6 men were hanged in Salem, Massachussetts for the crime of witchcraft.

Needless to say the hysteria of witch hunts struck hard for centuries throughout Europe and the colonies, leading to severe persecution, shunning, and often death for the accused men and women. Anything mysterious or hard to explain, like cows not producing milk or infant deaths, could be blamed on a witch. Science would later prove the real reasons for such events, but it would come too late to save the many people who were burned, hanged or drowned as witches. Pennsylvania avoided most of this madness, but not entirely, as Margret Mattson and Yeshro Hendrickson’s trial proves.

Written by Mary Barbagallo, Intern

Sources:

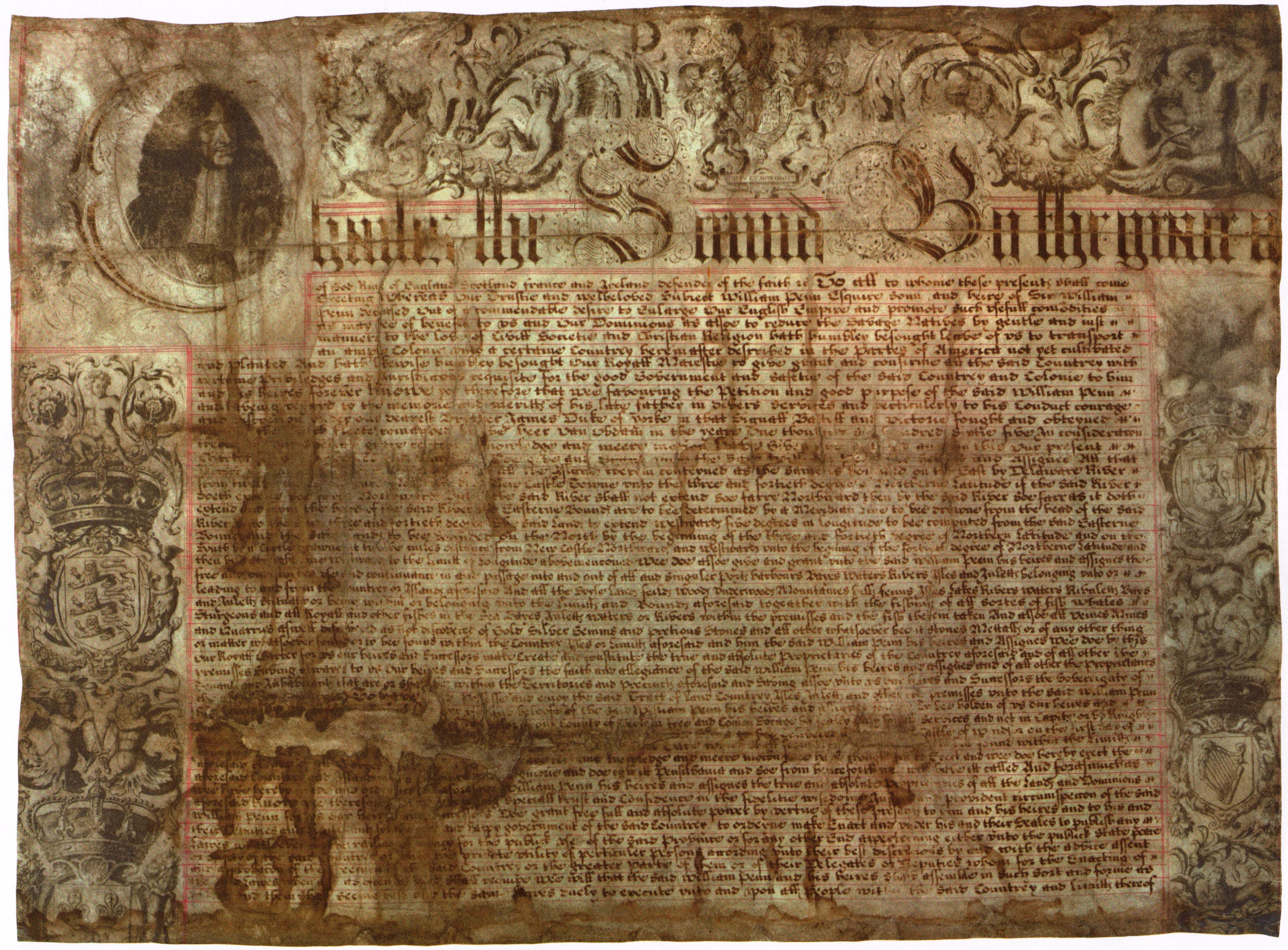

Pennsylvania Colonial Cases – Proprietor vs. Mattson

The Malleus Malficarum of Henrich Kramer and James Sprenger: Translated with an introduction by the Reverend Montague Summers, Dover Publication, Inc., New York, NY, 1971.

The Witch Hunts: A History of the Witch persecutions in Europe and North America, Robert Thurston, Pearson Education Ltd., United Kingdom, 2007.

“

“