Ann Shippen’s Story (Part II)

In an earlier post we shared the story of Ann Shippen, who at age 17 was living with the Penn family at Pennsbury Manor. Ann was being courted by two men, James Logan and Thomas Story, both loyal confidantes of William Penn and fellow Quakers. Ann’s father, Edward Shippen, voiced his opinion regarding the courtship and favored Thomas Story over James Logan. He thought Logan, who was 10 years older than Ann, to be too young, too naïve, and not successful enough to support his daughter. He preferred Thomas Story because he was more mature (20 years older than Ann), and as a Quaker minister and a member of the Provincial Council, was more established.

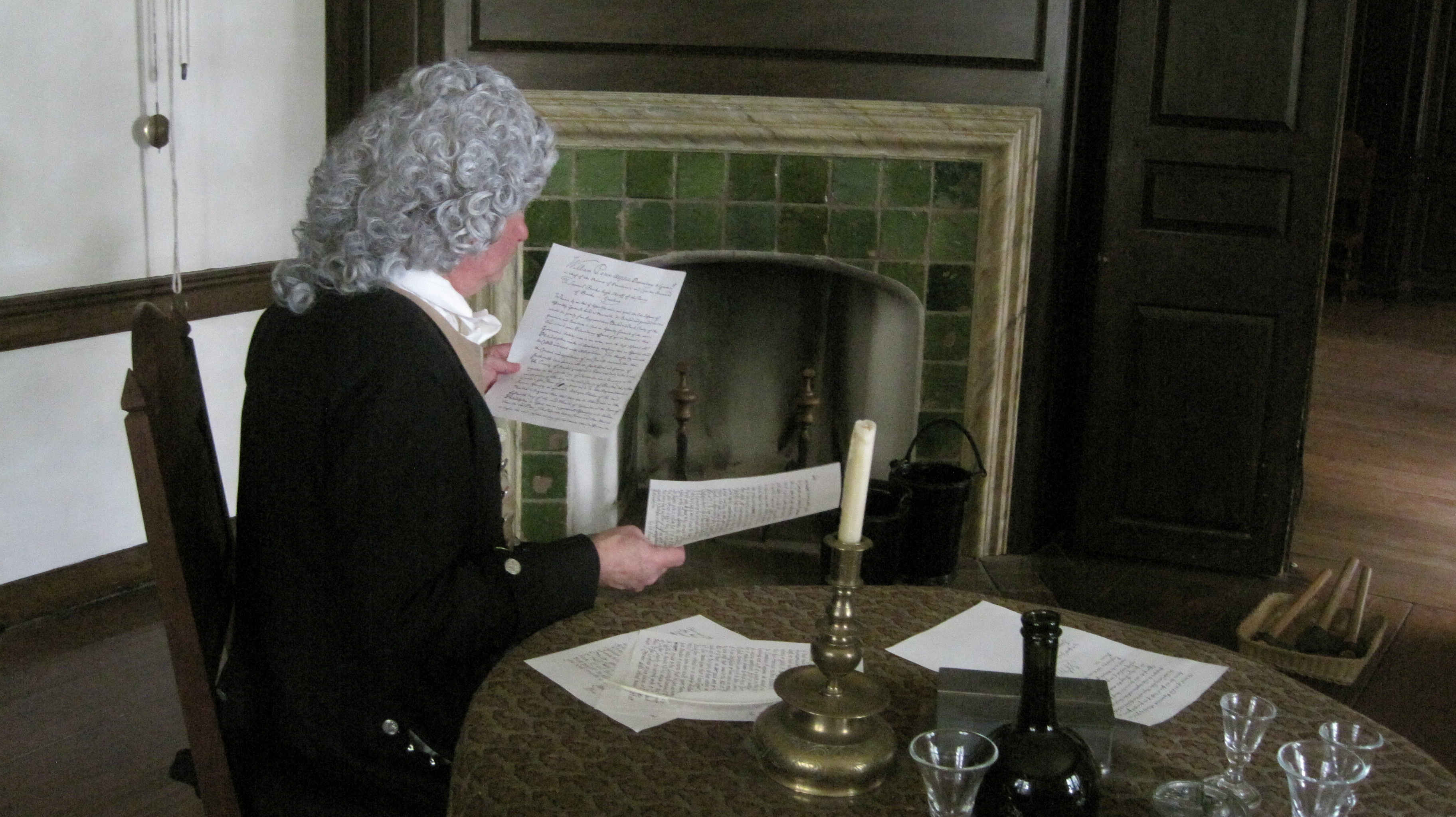

Despite the discouragement of Edward Shippen, Logan continued to court Ann at the same time as Story. Their competition for Ann’s hand in marriage became so well known in Philadelphia that William Penn wrote of his concern in this 1704 letter to James Logan –

“I am anxiously grieved for thy unhappy love for thy sake and my own, for T.S., [Thomas Story] and thy discord has been no service here any more than there.”

After several years of courtship from both James Logan and Thomas Story, Ann was finally convinced of Thomas Story’s love for her. Story confessed his love to her by saying that he had “ the patience beyond what was common,” and that he would, “reasonably try all or stretch upon the rack, which had no common heart, nor soul could be able to endure.” Ann overlooked the 20-year age difference, listened to her father, and finally accepted Thomas’s proposal.

The couple married in July, 1706 and lived in Philadelphia. Sadly, their marriage was short-lived. Ann died in 1710. There were no children. Thomas, who died in 1742, never remarried.

Melanie Hankins, Intern

Further Reading

John W. Jordan, Colonial and Revolutionary Families of America, 1978.

Albert Cook Myers, Hannah Logan’s Courtship: A True Narrative, 1904.

Craig W. Hortle, Lawmaking and Legislators in Pennsylvania: A Biographical Dictionary Volume Two 1710-1756, 1993.