Just as in the time of William Penn, the work was never done, and so too do we find our fourth post in regards to Dairying!

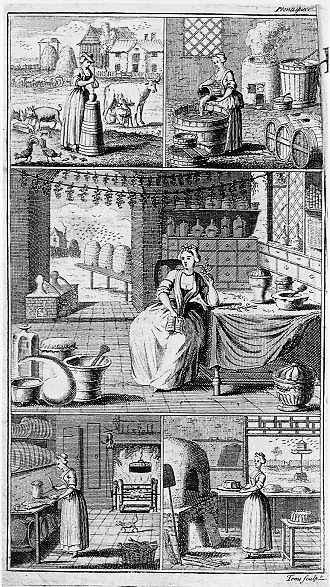

Our first posts covered the business of being a milk-maid, the history of dairying and cheese-making. Now let’s take a look at the importance of cream and butter, which held an important place at the table long before cheese was acceptable to anyone but “common folk.”

In these aristocratic households, their status and wealth meant their butter was made purely of cream. In addition, cream was used in pasties, dressings for meat, and custards.

The butter itself took on a purpose all its own in a number of different forms. Initially, butter was acceptable for children and the old, but not middle-aged gentlemen of higher stature like William Penn. Even the most basic thoughts for butter (such as being spread on bread) were something that came from Flemish practices, who were influenced by the Dutch on this matter. Eventually it became common practice for the English toward the late 16th to early 17th century.

The trend eventually went away from butter as a hard spread; as butter began to be melted and poured over vegetables, it became more prominent at the dinner table. Melted butter was also used for sauces on fish, meat, and other main dish delicacies. Moreover, it became an important element of preserving food, which was always important in regards to ensuring enough sustenance for the winter months. “Butter was used lavishly to seal the cooked food from contact with the air, and in order to ensure that no cracks appeared in the sealing, many pounds of butter were used in large households”. “The improved arts of preserving food also involved another use for butter, by filling pies after they had been cooked with melted butter to make an airtight seal, and filling jars and pots of cooked meat and fish in the same way. Thus they kept for days or weeks”.

Furthermore, just as cheese took hold and started to become an area specialty, so too did butter. It began to be made with less-expensive dairy products (whey, milk, town milk, etc), which allowed it’s accessibility to all classes. The variations in butter also came as a result the cows’ diets, which would affect the taste based on what was eaten. Fresh grass from the pasture was preferred for the best quality milk to turn to butter (just as it was with the milk to be used for cheese) yet, this was not always the case due to the large portion of cattle eating clover as well. Resultantly, this variation created noticeable differences and would often affect the flavoring and coloring of butter.

The dairy industry boomed and the growth of butter lead to its export from England from the 1630’s onward. The height of which was between 1638 and 1675. Does that mean we could perhaps call it… the bread and butter of the English economy? Oh c’mon, that’s funny!

Written by Mary Barbagallo, Intern

Further Reading:

Food in Early Modern England – Phases, Fads, Fashions 1500-1760, Joan Thirsk, Continuum Books, 2007, New York, NY