When many people think of the harvest, they think of autumn. But another important time for gathering crops, not to be forgotten, takes place in the heat of the summer!

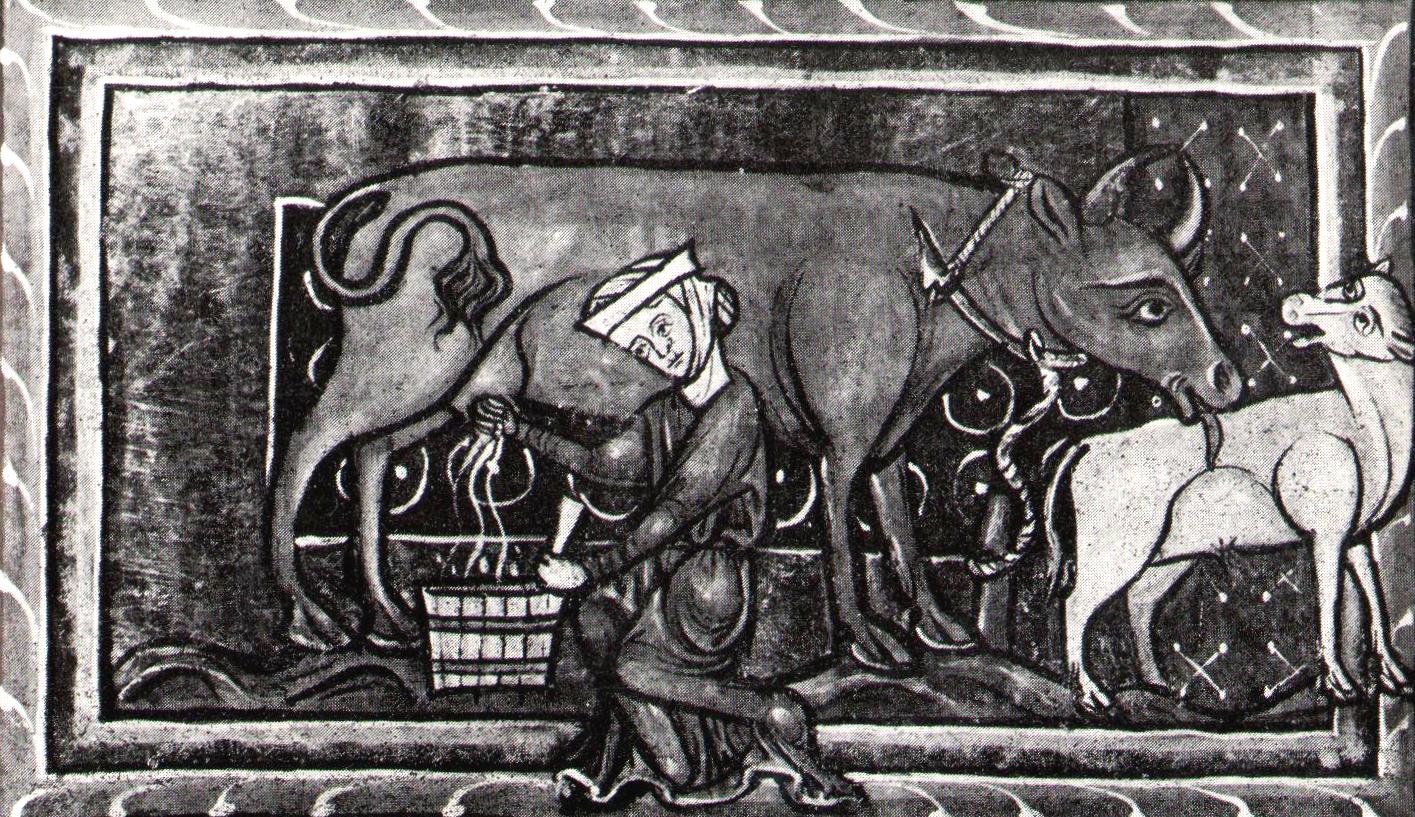

In an age where food wasn’t from the local supermarket, but from the land people lived on, it was important to use the soil to the best of its ability. With ground-breaking techniques (no pun intended!) of the time, farmers were able to work the land to provide maximum yield from the beginnings of spring, to the eve’s of winter.

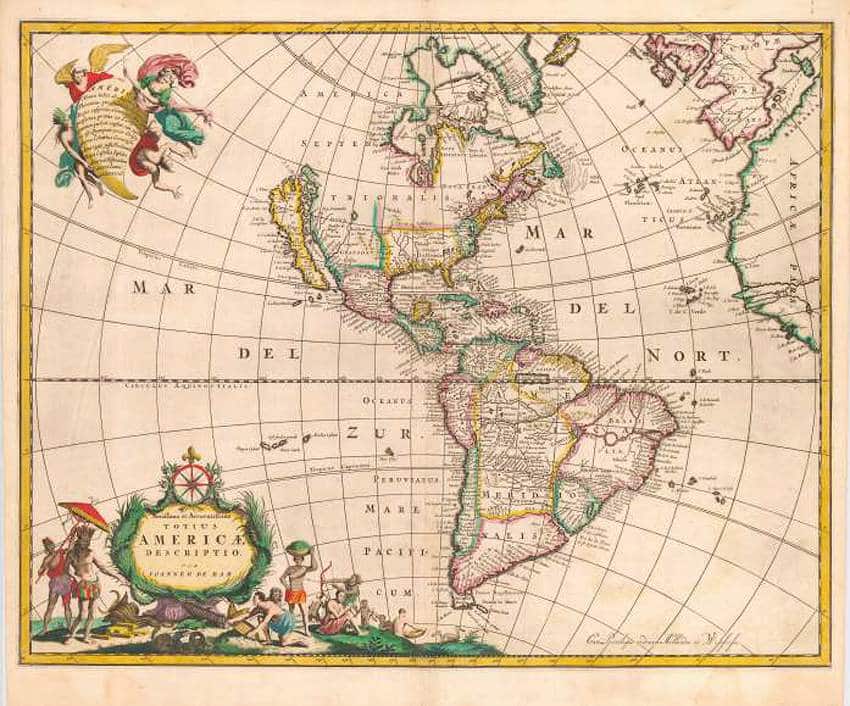

One important crop of colonial Pennsylvania was wheat. Of three varieties grown, winter and summer wheat were able to be harvested around the month of June, if weather had been good. Governor Penn even reports “they may sow eight acres; half with summer wheat and half with oats,” referring to successful agriculture production in his colony. Other summer crops include rye, hemp, barley, oats and flax.

In smaller kitchen gardens, more customized techniques could be applied to each plant being grown. Here at Pennsbury Manor we have a reconstruction of William Penn’s own kitchen garden. It was intended for raising vegetables, herbs, and anything else that could be found useful in the estates kitchen. Structures like “hot beds” were created to begin the germination of seeds in late winter. This wooden framework was filled with manure, and topped with a layer of soil; this bed could become as hot as 100°F in the coldest of winter. Once mature enough, they can be moved to garden beds.

Similar to the hot bed, the cold frame was a structure used to protect fragile herbs. This structure was enclosed with spare glass, matting or canvas. One would also find raised beds. This state of the art invention allowed planters to control the fertility of their soil and manage it accordingly.

With innovations such as these, the kitchen garden would be able to adapt to the seasons and continuously provide for the estate. In a time like Penn’s, it was always important to put time to its best use, even in the heat of the summer!

By Ray Tarasiewicz, Intern

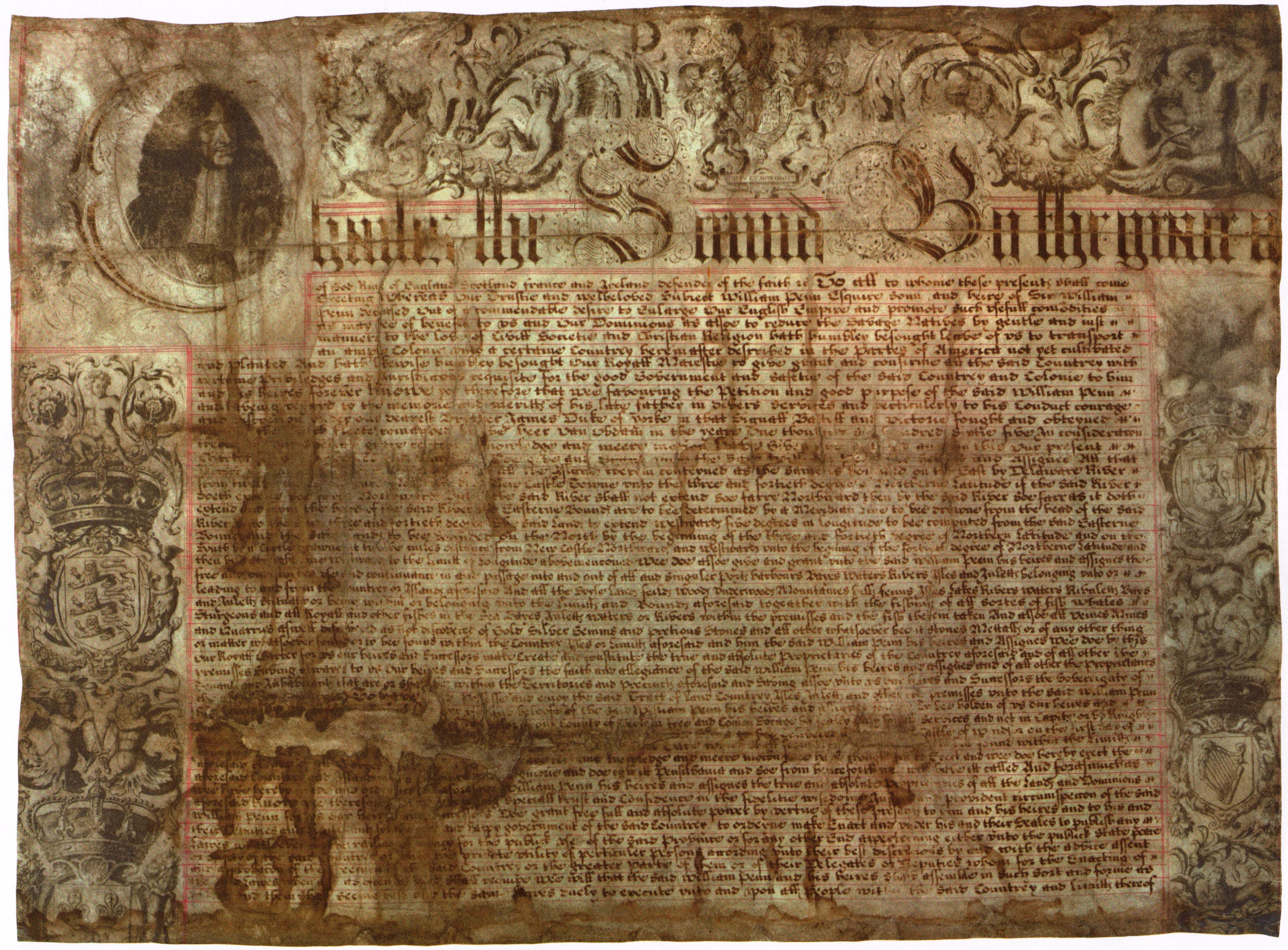

In similarity to the creation of quills, the manufacturing of ink varied as well. No two were perfectly alike, as there was usually a variation in ingredients and process. Produced from varied plant, animal, and mineral extracts; a common recipe (often produced by farmers as an additional source of income) consisted of oak galls (growths on oak leaves caused by insects), copperas (a naturally occurring, greenish, crystalline, hydrated ferrous sulfate, used in manufacturing of fertilizers and inks and water purification), and water. High in tannin and often also used for dying fabrics and tanning the ink was poisonous, but very permanent. As a result, it held up well over the years and has allowed us to examine documents and make numerous discoveries from writings made centuries ago. These discoveries include accounts of William Penn’s purchases of ink, amongst various other goods; it allows us to examine the development of handwriting and penmanship over time, as well as allowing us to examine ever changing grammar. So, the next time you pick up your quill and inkwell (or maybe just your ballpoint pen), think of the immense “mark” you can make!

In similarity to the creation of quills, the manufacturing of ink varied as well. No two were perfectly alike, as there was usually a variation in ingredients and process. Produced from varied plant, animal, and mineral extracts; a common recipe (often produced by farmers as an additional source of income) consisted of oak galls (growths on oak leaves caused by insects), copperas (a naturally occurring, greenish, crystalline, hydrated ferrous sulfate, used in manufacturing of fertilizers and inks and water purification), and water. High in tannin and often also used for dying fabrics and tanning the ink was poisonous, but very permanent. As a result, it held up well over the years and has allowed us to examine documents and make numerous discoveries from writings made centuries ago. These discoveries include accounts of William Penn’s purchases of ink, amongst various other goods; it allows us to examine the development of handwriting and penmanship over time, as well as allowing us to examine ever changing grammar. So, the next time you pick up your quill and inkwell (or maybe just your ballpoint pen), think of the immense “mark” you can make!

Back in May, we posted an article on the

Back in May, we posted an article on the