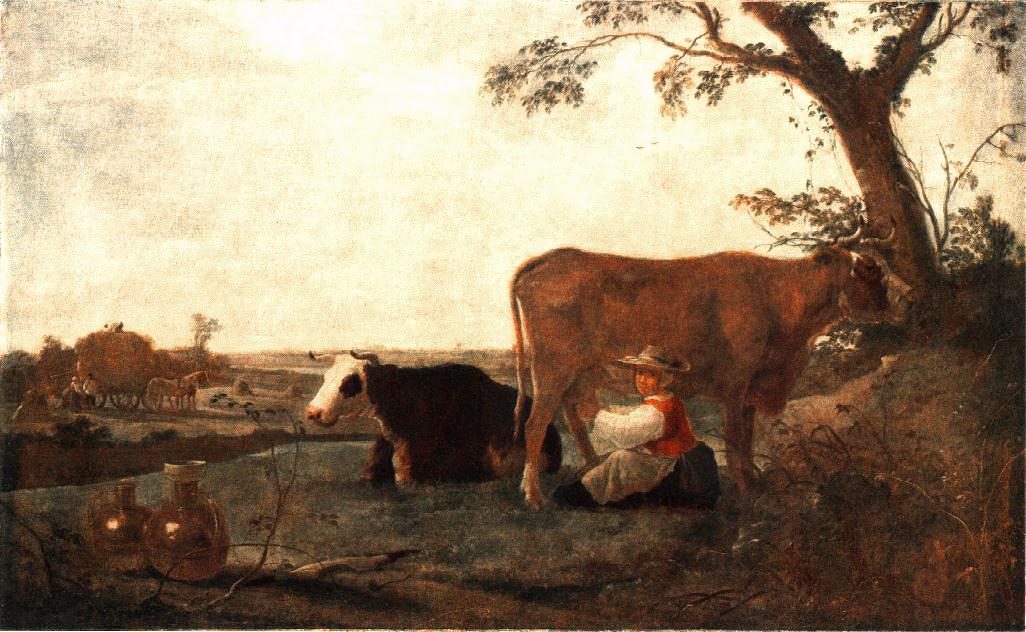

We’ve recently been discussing just how important dairying was, first as a career for the idyllic milkmaids and as a country business that was transported into towns (resulting in a more convenient, but poorer quality product). As those articles mentioned, there were a number of ways to prepare milk to be turned into various food resources. Today, cheese is a highly popular product (and a great way to preserve milk long-term), but it wasn’t always so fashionable!

A large amount of milk went into cheese making. Although dairy did take its role at the table of the 15th and 16th-century elite in a number of forms (of which the five most common were cream, curds, milk, buttermilk, and whey), the one seen at their table least was cheese. Cheese evolved from being a resource associated with poverty to being a sought-after staple for all social classes.

The main change that occurred in favor of cheese took place in the 1650’s when cheese became the primary reliance of the English army’s soldiers in Ireland. Also used to feed servants or humbler guests, it was found on ships because it lasted without deterioration, and thus it was a good option to send with both sailors and troops.

Further support for the consumption of dairy in the form of cheese came about as Englishmen saw cheese savored at the tables of high-ranking society members abroad. Initially startling the English elite, especially if served toasted and not cold, cheese eventually took hold at their table. This was especially so as the milk industry boomed and the different counties of England began refining the cheese making process to produce various types include what would be most similar to that of a sharp cheddar today. And, although the outcome was surely delicious, the process behind cheese making is less appealing.

Firstly, “a suckling calf’s stomach- bag was the usual source of rennet” (rennet-a dried extract made from the stomach lining of a ruminant, used to curdle milk). As a result cheese was made during the spring when a single calf could be sacrificed for the sake of cheese making and milk would be abundant. In conjunction, the process of cheese making was something simple that could be done at the home if you owned a household cow. Likewise, there was no need for special expensive equipment and the milk could be processed quickly. The resulting cheese making industry soon grew too and frequented the spring with the annual cheese making processes.

By Mary Barbagallo, Intern

Photographs by Hannah Howard, Volunteer Coordinator

Sources

Food and Drink in Britain – C. Anne Wilson, the Anchor Press Ltd., 1973, Great Britain

Food in Early Modern England – Phases, Fads, Fashions 1500-1760 – Joan Thirsk, Continuum Books, 2007, New York, NY

The American Heritage Dictionary, Second College Edition – Houghton Mifflin, 1985, Boston, MA