I really don’t like to milk cows. I can’t stand to churn butter. I know this is a shocking admission from a so-called history geek, but it’s true. So each spring I breathe a grateful sigh of relief that I can buy my milk and butter in containers at the grocery store!

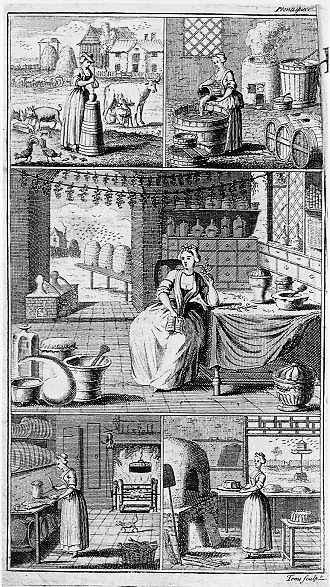

I wonder how the milk-maids of Pennsbury Manor felt about these chores in the 1680s. We don’t know their names, but we know they were here and that they were making butter: in 1684, William Penn suggested that James Harrison’s wife, Ann, supervise the maids in the dairy; the 1687 inventory includes churns and other butter-making equipment as well as 6 cows; there is strong evidence that a cow pen existed near the stable. We also know, given the exhausting nature of their work, that dairy maids had to be strong and sturdy to pump away at that churn!

Dairy products were an important part of the diet of people in Penn’s time with butter in particular being used liberally in many recipes. Butter was also preserved in crocks for later use, and even used as a preservative itself as it could create an airtight seal on crocks. And of course it could be sold at market, usually by the women who made the butter. Although buttermilk (the liquid resulting from butter production) could be turned into curds and whey for the household, “the best use of buttermilk for the able housewife is charitably to bestow it on the poor neighbours, whose wants do daily cry out for sustenance.” (Gervase Markham, The English Housewife, 1615) Who wouldn’t want to do this after being promised that “she shall find the profit thereof in a divine place?” Heaven for buttermilk? What a deal!

May was the peak of butter production. Housewives were advised to breed their cows to calve between March and April when the grass is nearly or at its richest. The resulting milk made the best butter. Later on in the year as the grass passed its prime (July), butter production was replaced by cheese-making – another lucrative product for households.

By 1701, the dairying equipment had disappeared from the inventory of Pennsbury Manor. William Penn’s account books have numerous entries for purchases of butter from local young women. Was butter not produced at Pennsbury any longer? Or did the demands of the Penn family and guests exceed production on the site? I am inclined to believe the latter as Penn still desired a dairy and a milk house. Making butter was an integral chore of an estate; it would be highly unlikely that there was no dairying at all taking place.

Pennsbury will have a milking cow demonstration on April 29, and a dairying demonstration on June 17. Both programs will take place between 1:00-4:00. Don’t look for me to be milking or churning!

By Mary Ellyn Kunz, Museum Educator and Former Milkmaid