“The gardiner is brisk at work. The Peach-Trees are much broken down with the weight of Fruit this Year.”

William Penn’s steward James Harrison reported this good news in October of 1686, but the same could be said of the fall harvest in 2012! Indian blood peaches, radishes, red and yellow cayenne peppers, squash, gourds, and culinary and medicinal herbs have all thrived this year in Penn’s kitchen garden.

According to Pennsbury’s gardener Mike Johnson, this is due in part to the recent restructuring of the garden’s fences. While Penn’s original garden covered about two acres of his estate, the smaller area has allowed the garden staff to protect the plants from pests and to interpret seventeenth and eighteenth-century garden activities more effectively for visitors.

You may be asking yourself, “What happens to all those fruits and vegetables?” Just as in Penn’s time, nothing goes to waste! Harvested crops will be used in cooking demonstrations, educational programs, and seed-saving for future planting.

Let’s follow the path of the dipping gourd, which has yielded a particularly plentiful harvest this year. From the garden, the dipping gourds will make their way into storage to dry until next summer. At that time, our summer campers will remove the seeds and return them to the gardener so they can be planted. Once the seeds are removed, each gourd will be fashioned into a ladle-like tool used for watering plants. In a time when metal watering cans were expensive, being able to grow one’s own irrigation tools was certainly a favorable alternative.

- Dried gourds make excellent dippers for the cistern. Gourds and thumb-pots are favorite 17th-century tools kids can use as they water the garden’s many plants.

2012 was also a “hot” year for red and yellow cayenne peppers. Growing cayenne peppers has given the garden staff an opportunity to interpret contradicting horticultural ideas, as not everyone on the estate would have eaten them. African slaves living at Pennsbury had their own culinary culture and probably would have cultivated cayenne peppers as a food source. However, the Penn family and Pennsylvania’s other English residents would have considered them to be primarily ornamental plants with some medicinal and culinary value. For example, cayenne pepper and other spices would have been added to hot chocolate for an exotic burst of spicy flavor.

The fall harvest is well under way and will continue for the next few weeks. On your next visit to Pennsbury, take a walk through the garden and reflect on the efforts of our gardeners, past and present. They cultivated food for the table, medicine for those who were sick, and even tools for future growing seasons. Autumn is the perfect time to celebrate their achievements!

By Danielle Lehr, Volunteer and Intern

Back in May, we posted an article on the

Back in May, we posted an article on the

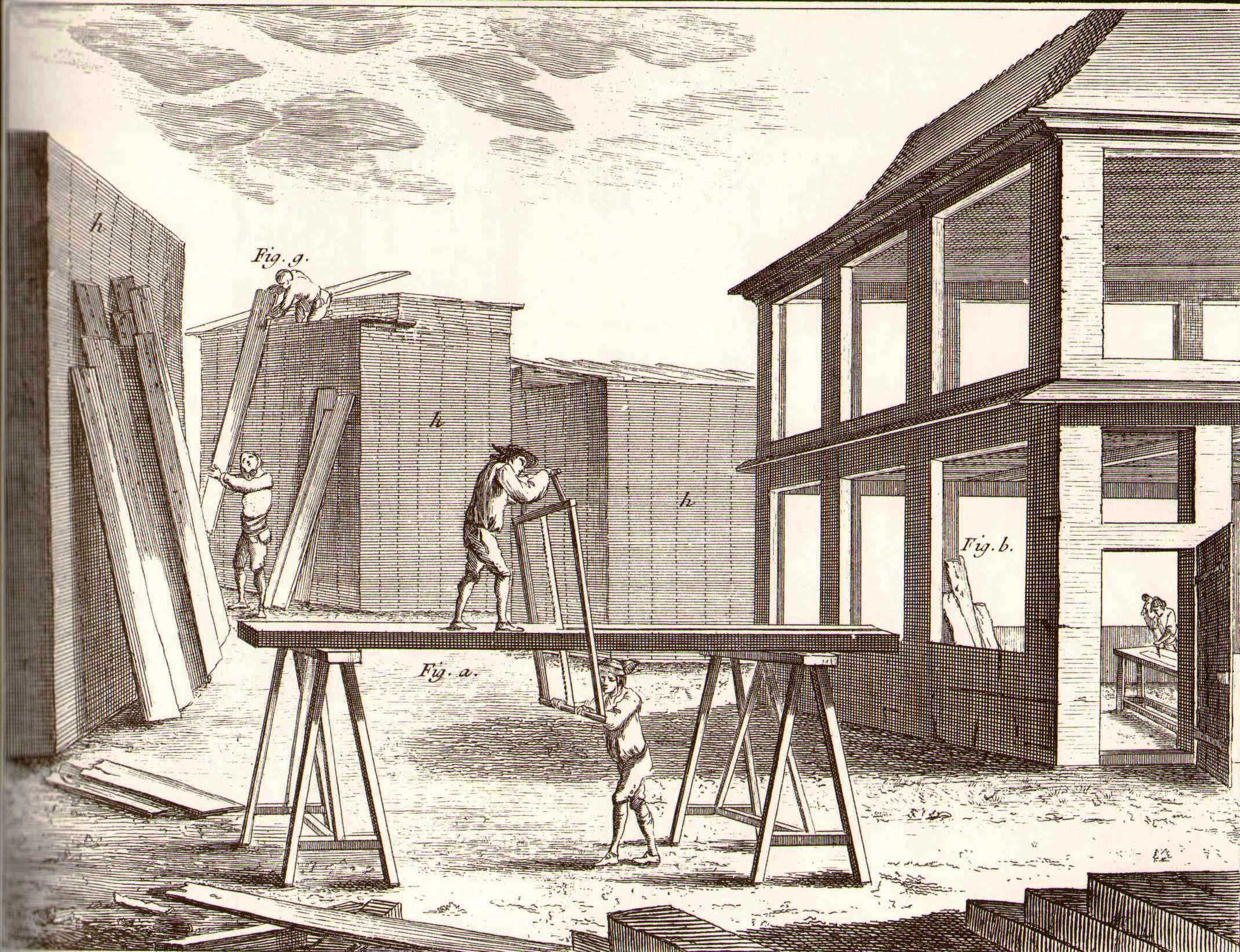

Those of you that have walked the grounds of Pennsbury may have seen a building called The Worker’s Cottage. This reconstructed outbuilding’s original purpose or even existence is unknown, but we use it to talk about the laboring class’s lifestyle in early colonial Pennsylvania. Most people did not live as luxuriously as William Penn’s family. Most homeowners, or people who worked as an apprentice or slave for a homeowner, lived in a 1-2 room house similar to this.

Those of you that have walked the grounds of Pennsbury may have seen a building called The Worker’s Cottage. This reconstructed outbuilding’s original purpose or even existence is unknown, but we use it to talk about the laboring class’s lifestyle in early colonial Pennsylvania. Most people did not live as luxuriously as William Penn’s family. Most homeowners, or people who worked as an apprentice or slave for a homeowner, lived in a 1-2 room house similar to this.

Place a larger clean pot on the ground and drape cheesecloth or piece of linen across the top. We learned that this works best if the cloth is strapped to the sides with some twine or rope. If working inside, cover the floor with washable cloth or newspapers to prevent any mess or damage.

Place a larger clean pot on the ground and drape cheesecloth or piece of linen across the top. We learned that this works best if the cloth is strapped to the sides with some twine or rope. If working inside, cover the floor with washable cloth or newspapers to prevent any mess or damage.